Song of Toledo – II

Introduction

In 711 C.E., an army some 10,000 strong, comprised of Arabs and Berbers, crossed the Mediterranean from northern Africa and landed on the Iberian Peninsula at what later became known as Gibraltar. That invasion marked the beginning of a two-decade sweep into Europe by Muslims – later known as Moors – that ended on the north side of the Pyrenees mountains, in present-day southern France, when the Moorish army was defeated in 732 by a Frankish army under Charles Martel. All that was left to the Christian descendants of the Visigoths who had ruled the entire peninsula for 300 years was a narrow strip of territory extending along the northern Atlantic coast.

In 1085, the Christian king, Alfonso VI, scored the most significant victory since the defeat of the Visigoths when he re-captured Toledo, the former capital of Visigothic Hispania and the See of the Roman Catholic Church for the entire country.

This victory, which many consider the true beginning of the so-called “Reconquista”, the centuries-long effort reclaiming the entire peninsula for its former Christian rulers, provides the backdrop for Song of Toledo. As often happened throughout early medieval Spain, actions taken by one ethnic or religious group often resulted primarily in reversing actions taken by another group. For example, in 1086, following his recapture of the city the previous year, Alfonso VI reconsecrated what was then Toledo’s main mosque as the cathedral it had been over 300 years before. This historic event lies at the heart of Song of Toledo, which follows the lives of two boys, one Christian and one Muslim.

The story opens in a monastery to the north of Toledo, where Pelayo, a young novice, learns he is about to be introduced to a world far beyond the confines of the secluded monastery he has called home since being orphaned years before.

At the same time, Faisal, a young Muslim boy, is realizing that the life he had planned to live out in his beloved home of Tulaytula (the Arabic name for Toledo) has slipped away forever.

Despite the chilly start, it had become a warm day for late November, though the breeze was still noticeably cool. As the sun climbed in the sky, the morning mist slowly pulled back to reveal that they had indeed left behind the green hills to which Pelayo was accustomed. Now, they were surrounded on all sides by seemingly endless stretches of short grass that was quickly dying as winter approached. After their short exchange, Brother Bernardo fell silent again, and Pelayo wondered if the older monk had truly been interested in where he had come from or if the goal of his question had been simply to pass the time.

“Are we in a hurry, Brother?” Pelayo finally asked. He was growing tired from the pace, and his cowl had begun to droop and drag in the dirt.

Brother Bernard smiled broadly, his cheeks seeming to peel back from the center of his face.

“I suppose we are, Pelayo,” he replied. “But are we moving too fast?”

“No, Brother,” the boy tried to lie. “I was just wondering, as you seem to be rushing.”

“Why don’t we rest a while, then? The archbishop will be arriving in Morela today, as well, but we will be there by late afternoon.”

“The archbishop, Brother?” Pelayo asked in surprise.

“Yes, we’re meeting him there along with a fairly sizable party. Didn’t Abbot Esteban tell you that?”

“Why, I don’t remember, Brother,” Pelayo replied after a moment. “I was very sleepy last night. I guess I just assumed he was already in Toledo.”

“Oh, no,” Brother Bernardo replied. “You see, he is also from Cluny. King Alfonso, in consultation with Abbot Hugh – my abbot at Cluny, that is – has appointed him archbishop some weeks back, but as you can imagine it is a long trip from Cluny to Toledo. I have come with them myself.”

Brother Bernardo’s pace slowed, and then finally he stopped.

“Yes, let’s rest,” he said quietly. “I am sure we are well past Terce anyway.”

He glanced up at the sun overhead, then slipped his bag off his shoulder and looked to the ground for a place to sit.

“I must confess, Pelayo, that I have traveled a great deal in my life, but I have never mastered the art of telling time by the sun. I am sure that I have missed more of the Divine Hours than I dare to imagine.”

As they knelt in the field, the bright sun above indicating that it was already nearing mid-day, Brother Bernardo reached into the cloth sack that had been draped over his shoulder since the monastery and pulled out the book Pelayo had seen him with in the abbot’s office the night before. At first glance, it appeared to be a normal, well-worn book, a standard brown cover opening up to thick, vellum pages. As he began to flip slowly through the pages, however, Pelayo found himself peering ever more closely at writing he had never seen before. Despite all the copying of texts had done over the previous years he recognized none of the words. At least he assumed they were words, though they were like nothing he had ever seen before.

“Brother,” he asked, pointing at the scratching on the pages. “What is that?”

Brother Bernardo smiled, then began turning more steadily through the dry, thick pages.

“This is the breviary of my youth, Pelayo,” he said.

“But that is not Latin, Brother,” Pelayo protested. “I don’t know what it is, but I know it is not Latin. How, then, can it be a book of prayer?”

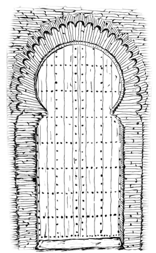

“Well,” Brother Bernardo began slowly, “because it is the book in which I first learned the Christian faith. You see, Pelayo, I was born in Toledo. And I grew up there. I am a Christian, but my family has lived for generations under the rule of the Moorish kings, and while I certainly speak and read Latin, as well as this language you and I share, my first language was Arabic. That’s what you see in these pages.”

He held the book closer to Pelayo so that he could see the script more clearly. The boy ran his finger across the page, as if just by looking more closely he could magically understand the words before him.

“Ah, that’s your first mistake, my son,” Brother Bernardo laughed. “Unlike Latin, Arabic is not read across the page from left to right, but from right to left.”

Having spent years, day after day, painstakingly learning the language of the Church Fathers, Pelayo immediately felt a strange sense of betrayal. In the next moment, however, he recognized that that was probably a foolish reaction. After all, the Gospel had been spread throughout most of the world that was once part of the Roman Empire. There was no shortage of variety to the languages used locally across that vast landscape. Why, then, would he have thought that there was no other language but Latin in which to preach the Gospel? Perhaps it was because Brother Bernardo did not say that the text in his hand was merely a collection of local prayers. Rather, by calling it his breviary, which was the monastic prayer book, he was clearly designating it as text on a higher order than a simple collection of prayers. How, then, could it be in something other than the language of the Church? Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, how could it be in the language of the same heretics who had invaded Hispania centuries before?

Still, while this discovery may have surprised Pelayo, he could not help but notice how much pleasure Brother Bernardo derived from the text in his hand. The movement of his lips was barely discernible, and it was clear that as he turned randomly through the pages he was reading aloud in a voice audible only to himself, just like the monks at Morela. The boy was still looking at the older monk’s face when the man looked up and saw Pelayo watching him.

“You see, Pelayo,” he said with a smile, “your presence on this trip is a happy accident to me.”

He hesitated a moment, glancing off across the brown, flat field to the hills at the horizon.

“Actually, that’s a misstatement, isn’t it,” he finally continued. He smiled at the boy again and shrugged. “It is a happy accident for me, but God must have had plans for you of which I was not aware. My intent in coming to Morela was only to retrieve this book from Abbot Esteban.”

“Abbot Esteban?” Pelayo said with a start. “What does he have to do with this?”

“He is also from Toledo,” Brother Bernardo replied. “We left our beloved home together nearly 20 years ago, during a period when, despite what al-Mamun’s men were saying publicly, it was clear that we Christians were going to be made increasingly uncomfortable, no matter how long our families had lived in that city.

“al-Mamun, Brother?” Pelayo asked, stumbling over the strange sounding name.

“Yes, he was the king of Toledo and all those cities that were beholden to him,” Brother Bernardo replied. “I wouldn’t worry so much about that, though, if I were you. King Alfonso has more than secured his grasp on the city. Besides, politics is not our concern. What is important is that now we will be able to reclaim our heritage. You see, while Abbot Esteban and I left Toledo together, along with others from our home, we traveled only as far as Morela. There, we encountered a handful of other monks who had come from the north to establish a monastery. Abbot Esteban felt called to stay with them so that he could be nearer to our home. For reasons I need not go into, however, I had set my sights on Cluny, and not knowing what lay in store for me I asked Abbot Esteban to keep this breviary. And that’s why I came to see him.”

He glanced back down and flipped through some more pages.

“But we did not stop so that I could give you a history lesson, Pelayo,” he said without looking up. “Would you mind if I offered prayers for both of us from this? Trust me, they are prayers to our Lord, if in a different language than you are accustomed to.”

Seeing no reason to object, Pelayo nodded slowly and watched as Brother Bernardo leafed through the pages. Finally reaching a page that seemed to satisfy him, he cleared his throat and began. For several moments, Pelayo tried to listen clearly to the words that were coming out of Brother Bernardo’s mouth. He had no choice but to trust what Brother Bernardo had told him – that the prayers he was reciting were indeed prayers to the one true God. Still, as Brother Bernardo sat and slowly read through page after page, he could not help but think that the older monk could just as easily be beseeching Satan himself.

Finally, after a quarter hour, Brother Bernardo suddenly closed the book and stood up.

“Shall we be on our way, Pelayo?” he asked as he wiped the dust from the ground off his cowl.

“Yes, certainly,” the boy replied, scrambling to his feet.

“After all,” the Brother continued, “I said we’d be there before the sun went down, and I intend to keep to that schedule.”

He had grown up shaping meticulous plans for his future, but a year earlier, in the spring of 477, just before he turned 15, Faisal learned how plans could change, how quickly the world could change, and how unexpectedly, too, even in Tulaytula. He had now been an apprentice to his father for a couple of years, long enough, he believed, that it seemed reasonable for him to begin to look forward in earnest to the day when he might take a position for himself. He wasn’t sure precisely what that position might be, but the thought of a position from which he might pursue his own ambitions brought him great satisfaction, as well as no small amount of anticipation.

But that was a year of great change in Tulaytula, the likes of which Faisal had never imagined possible. Since the previous autumn, the Christian king from the north, Alfonso VI, had been set up in camp on the lands to the south of the city, which the Christians called Toledo. His goal was to intimidate Tulaytula’s king, Yahya al-Qadir, grandson of the great al-Ma’mun, into handing the city over to him. It was a hard winter. Food was scarce and business in the markets was slow, as the city was vying with Alfonso’s army for provisions from the surrounding countryside. Moreover, it was a period of great unrest among the taifa kingdoms that were scattered across the northern boundaries of Al-Andalus. What put al-Qadir in particular peril was the fact that two of his allies, Abu Bakr of Valencia and al-Mutamin of Zaragoza, both fell ill and died as Alfonso was waiting for al-Qadir’s surrender.

And then it happened. In the spring of 477, al-Qadir surrendered and the Castilian king rode into the city at the head of an army, reclaiming Tulaytula for the Christians for the first time in 300 years. Faisal would never forget the shock that raced throughout the city. He had heard his father talking with his colleagues about the negotiations that the king was carrying out, but no one expected his capitulation to be so sudden and so complete. Naturally, the king claimed that he’d had no choice; without his allies in Valencia and Zaragoza, he could not be expected to stand up to Alfonso himself. Furthermore, the siege had depleted their supplies, which must have factored into the king’s considerations, for as soon as al-Qadir capitulated wagons began rolling into the city.

In some ways, very little changed when the Christian king claimed the city, but in other ways things changed too much for many of their friends, as well as his father’s colleagues, to accept. They were allowed to remain as more or less free citizens, keeping both their property and the right to practice their faith. And those who wished to leave could do so and take their belongings with them. Still, Muslims, along with the city’s Jews, were now forced to pay the annual head tax, which was traditionally paid by the faith communities who did not rule the city. At first, all their mosques remained in their hands except for the main Friday mosque near Faisal’s grandfather’s house. That mosque became the property of the new king, and he was free to do with it as he wished.

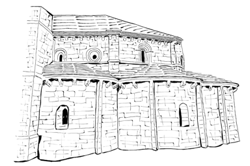

Soon after the change in rule, the families of many of Faisal’s friends took what property they could and moved south to Qurtuba, which, when the Christians held the city centuries before, they had called Córdoba. Faisal’s father opted to stay on with the administration as muhtasib, but he now knew he could be dismissed at any moment. As for Faisal, he had the hope of youth that the change would be temporary, but he couldn’t deny that the changes underway, if they continued for long, would change Tulaytula forever. Perhaps the uncertainty surrounding the city’s mosques was what concerned him the most. The mosque at which he had worshipped since his father taught him salaat stood at the base of the street on which his house was located. It was not nearly the size of many of the city’s other mosques, but except for Fridays, when Faisal accompanied his father to salaat in the main mosque, he always tried to be near Bab-al-Mardum, as the neighborhood mosque had been called since its construction nearly 100 years before Faisal was born. For one thing, it was obviously in convenient proximity to his home, but it also had a beautiful garden, including a fountain, which looked out over the southern wall of the city and across the Tajo River. And after salaat, from that garden Faisal fashioned no small number of his plans for the future as he gazed out across the river to the flat meseta beyond.

But change did indeed come to Bab-al-Mardum. While it remained officially in Muslim hands, somehow, a preposterous story began to circulate that when King Alfonso was entering the city after al-Qadir had surrendered, his horse suddenly knelt at the doorway to the mosque. Faisal knew that this was an absurd tale spun by propagandists determined to undermine the Muslim claim to the city. Not satisfied with such a lie, the king’s advisers then claimed that a crucifix had been found behind a wall inside the mosque, and that a candle had been kept burning in front of the crucifix since the Visigoths were driven out three centuries ago. It was true that the mosque sat on the site of a Visigothic church, but Faisal assumed there was little left of the church when the mosque was built, and he was more confident that there was no hidden compartment with a figure of the prophet Jesus. Nonetheless, these facts did little to prevent the story from taking hold quickly among Tulaytula’s Christian population, and emboldened by the presence of their new king they began to ask for the chance to take the mosque in which Faisal prayed daily and transform it into a Christian church.

Despite this and other instances of lingering uncertainty, Faisal had to admit that after some initial changes it seemed that life might return to something approaching normalcy. Or, at least, so it felt to him for a few months after the Christians had taken over. While he may not have been quite as optimistic about his future as he had been before, he thought that so long as his father held his job, and as long as he was able to assist him, it seemed reasonable to hope that change might come again, and this time back in the favor of the Muslims.